The Pioneer Years - The Birth of Formation Football

At the end of the 1880s, football had modified and expanded it’s rulebook to maintain the interest of the spectators and to keep an equal playing field between the offense and defense. What began as an wide open game with players spread across the entire field for long lateral passes had collapsed to a shoulder to shoulder shoving affair on the line of scrimmage complimented with short bursts up the middle by the backs. This was the direct result of two rules: lineman could no longer block with their arms or hands, and defenders were now able to tackle below the waist, making it nearly impossible for evasive open field running.

Over a century later, football, for the most part, has reverted back to the wide open style of play that emphasizes space, speed and agility as opposed to using brute strength in tight distances to tear open holes for the runner. The influence of spread formations has turned football into a high flying spectacle that’s perfectly suited for the era of fantasy football and high definition television. Even though the running game has been adapted to survive and remain a necessary dimension of football, the popularity and efficiency of the modern passing game has captured the imagination of the coaches and fans, and has become the cornerstone of any successful offense.

But in the decade before the legalization of the forward pass, coaches, not restricted by the line of scrimmage and motion rules of today’s game, created dynamic and highly organized tactics to counteract this compact “plunge up the middle” game that football had become. These would come to be known as mass momentum plays that featured uniquely designed formations that charged at the weakest point of the defense before the snap to open up running lanes the ball carriers.

interference

Princeton’s “V Trick”

The concept of these mass momentum plays finds its way back to the “V-trick” play in the Princeton-Pennsylvania match up in 1884. Kickoffs in those days didn’t have to travel at least ten yards, so teams would kick the ball to themselves and charge downfield and lateral the ball once the opposition closed in. In this game, however, halfback Alfred Baker stood behind his teammates as they locked arms and formed a wedge in front of him, with the apex pointed towards Penn, and he kicked the ball up to himself and proceeded to charge at Penn. Princeton’s experiment worked well as they won 31-0. The V-trick would lay dormant for a few years due to the offside rule that prohibited players from being between the ball carrier and the goal line. The rule was inconsistently applied, so teams felt that it would be an unnecessary risk for the fear of potentially being penalized.

Over the next couple of years, blocking, known as “interference” in that time, became an accepted practice by both lineman and backs. With interference legalized, the V-trick had been revived by Princeton to great success against Harvard in 1886, but would be exploited by Yale as they attacked the apex of the wedge, while the remaining teammates crashed down on the sides. Yale used another method in 1888 that called for their freshman guard Walter “Pudge” Heffelfinger (considered the first professional football player) to leap over the apex man to tackle to the runner.

Given the new the rules that contracted the game, teams were forced to reevaluate their positioning and alignment. Going back to 1882, a typical formation would see seven forwards spread out, a quarterback stationed behind the center, two halfbacks and a full back. Some teams would replace the seventh lineman with a either third halfback or “three quarter back.” Now, teams aligned themselves into what would come to be known as the T Formation. Lineman, having to keep their arms at their sides, crouched low to the ground and lunged forward with their shoulders to block, and backs came closer to the line of scrimmage to get protection from the lineman.

Though these were common formations, they were not the result of rules that required teams to have a certain amount of men on the line of scrimmage, but rather influenced by the Rugby scrum that placed a certain amount of forwards in the scrum with the backs spread out. In 1888, with no rules to limit player movement before the snap and needing only the center to be stationed on the line of scrimmage, coaches would now bring football strategy to it’s highest point yet.

Wedge Formations

In 1889, Walter Camp adopted and modified the wedge for Yale, only this time it was not just used on kickoffs, but rather used on plays from scrimmage. His version of the wedge was known as the “shoving wedge.” Football historian Alexander Weyand described Camp’s formation in The Saga of American Football:

The players ranged themselves in a wedge with only the center on the line of scrimmage. Each man placed his hands on the hips of the man in front. When the ball was snapped, the players closed in tight and shoved. The ball carrier was protected on all sides. A trick, later introduced by [Amos Alonzo] Stagg, provided for a trailer to whom the ball could be tossed.

Yale’s Shoving Wedge

The shoving wedge was not the only progress Yale made when it came to interference. When lined up in a standard T formation, Yale instituted what would be known today as the “pulling guard.” Parke Davis, in his book Football: The Intercollegiate Game, states, “The ingeniousness of the Blue’s methods lay in the employment of a heavy lineman to lead the interference, who sprang from his position on the line at the snap of the ball…” Yale guards Pudge Heffelfinger and George W. Woodruff were at the forefront of this pulling concept, and garnered much recognition for their blocking ability on end runs, as well as for their willingness to push and pull the ball carrier through the defense.

The next two years would see various programs implementing their own variation of these concepts, such as coach John Heisman’s wrinkle to pull both guards from the line on end runs. The most experimental approach thus far that would revolutionize formation football, however, would be the ends back formation introduced by Amos Alonzo Stagg.

Stagg’s Ends Back Formation

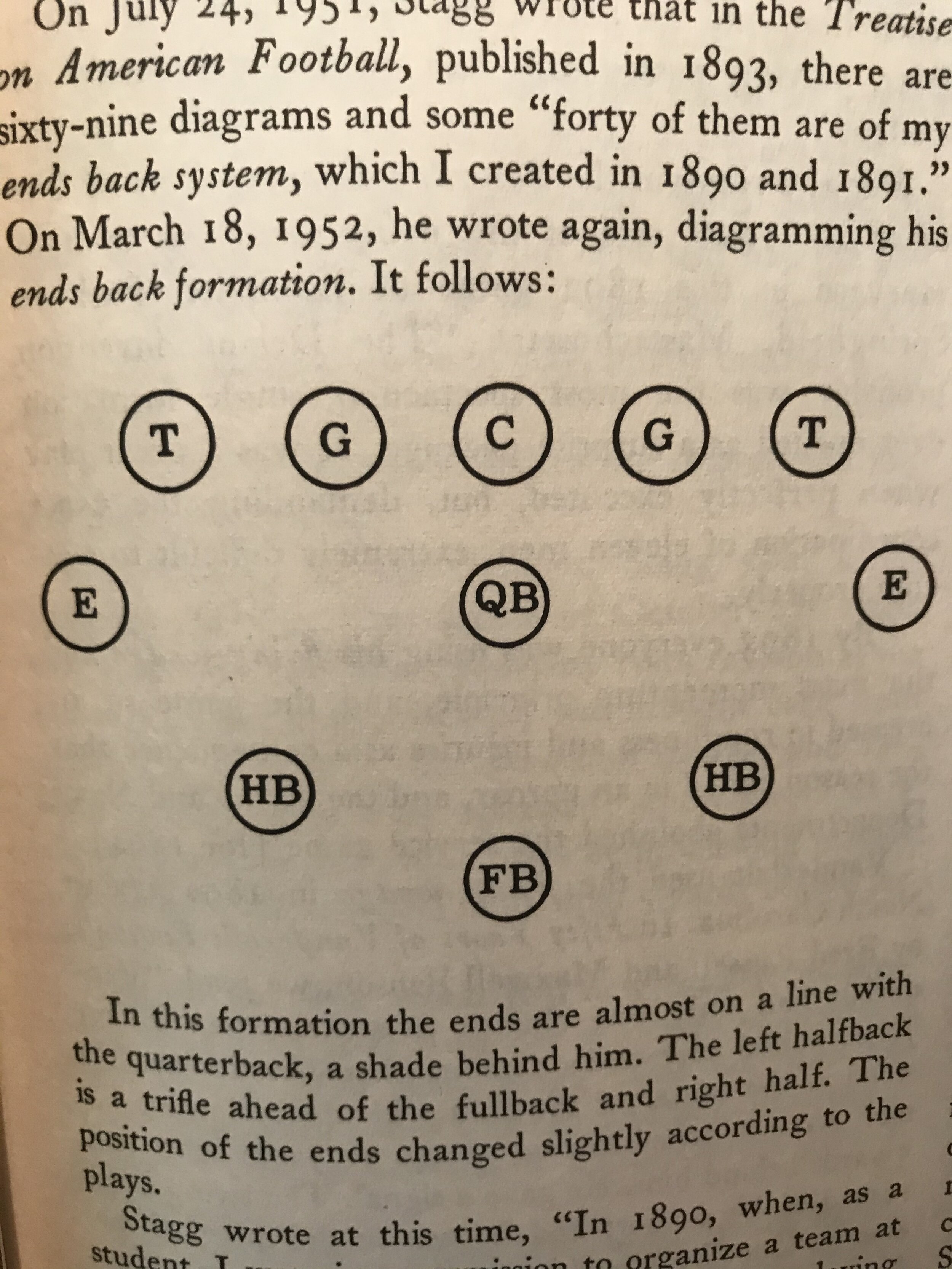

Stagg, coaching while attending the Springfield YMCA college in Massachusetts in 1980, took both ends off of the line of scrimmage and placed them in the backfield, a shade behind the quarterback, to act as lead interferers and pushers on both off tackle runs and up the middle plays through the center. In addition to blocking, the ends were also called upon to run with the ball on what eventually become known as the reverse and end-around plays. Stagg claimed to have used this formation against Harvard and Yale in the 1890 and 1891 season with great success. Stagg also invented the turtleback formation, in which the offense would line up in the shape of an oval at a designated point on the line. At the snap, the formation revolved to an end, deceiving the aggressive defense as the ball carrier sprinted down the open field.

But while Stagg’s unique formations would be an important landmark for the development of formation football, it wouldn’t be until these mass formations would be married with pre snap motion that would elevate football’s strategy to the complexity of chess. It would only take a chess master and military historian that never witnessed the game until his mid thirties to make this come to fruition.

Flying interference

Lorin F. Deland, born in 1855, was a man of great wealth who established a multitude of different businesses in a variety of different sectors. Also a man of many different interests, Deland was particularly interested in chess and military campaigns used throughout history.

Deland’s fascination with strategy would eventually find himself drawn to the gridiron. A Boston local, Deland has witnessed Harvard’s football team in action, and was curious to experiment to see if the military tactics that he researched could be applied to the gridiron, most notably Napoleon Bonaparte’s “mass multiplied by rapidity” theory. Deland was given permission by Harvard team captain Bernie Trafford to join them to put his hypothesis to the test.

The opportunity would arrive in the classic Harvard-Yale rivalry game in the 1892 season. The diagram to the left illustrates the formation that took Yale completely by surprise. At Trafford’s signal, both groups started for the ball and converged for form a wedge and Trafford kicked the ball to himself as the wedge engulfed him, before passing the ball to a teammate who got close to the goal line. Stagg would claim that, “the Deland invention probably was the most spectacular single formation ever opened in a surprise package.

With this new innovation, coaches across the country were pushing the boundaries of their imagination and took advantage of the unrestricted scrimmage rules to try everything under the sun in preparation for the 1893 season. As was common in college football at that time, the northeast would produce yet another visionary coach in former Yale guard George W. Woodruff, who became the head coach of the University of Pennsylvania in 1892. Woodruff had been working on variations of the flying interference play since he was hired, but chose not to reveal them until Penn’s game against his alma mater. Once the matchup with Yale arrived in 1893, Penn deployed their flying interference play in which an end and a tackle started before the ball was snapped. Once they got behind the center, the ball was put into play, and they joined hands with the full back and a halfback to create a passage at the edge.

Tackle Tandem Formation

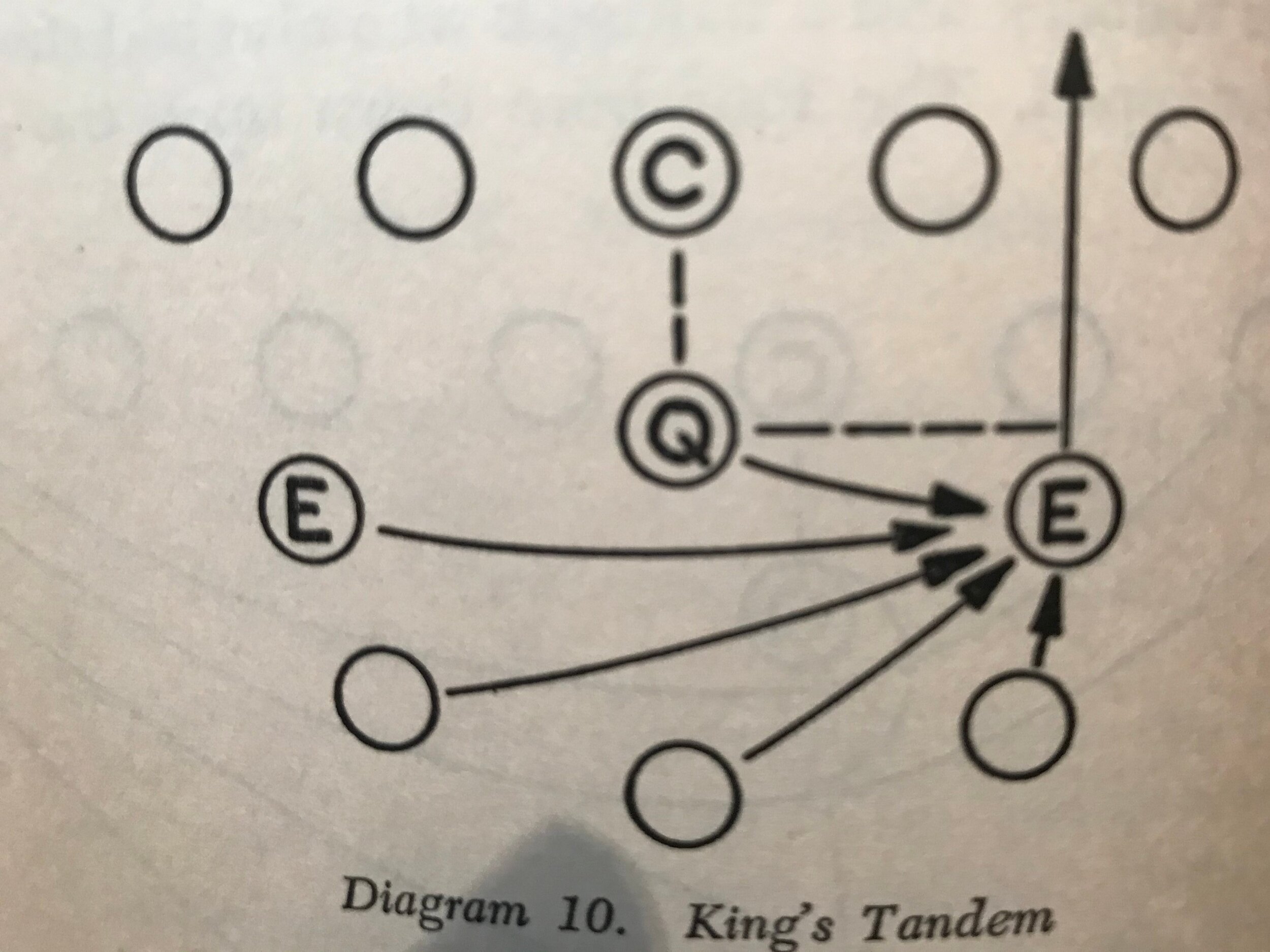

Meanwhile, Princeton and Yale were drawing up “chess board” formations themselves. Princeton team captain Philip King brought his ends from the line of scrimmage into the backfield, similar to the ends back formation created by Stagg, only in this formation the ends were stationed behind the tackles rather than shading to the outside edge. This became known as the tackle-tandem formation, and was versatile for attacking anywhere along the line. Yale, the other hand, took the Deland’s flying interference on the kick off and directly applied it to a scrimmage play. Aside from the center and the two guards, Yale took the backs, tackles and ends and formed a wedge fifteen yards behind the line. They began charging toward the line and the ball was snapped right as they reached their designated target on the line.

Demands for reform

As is common throughout the history of American football, the rules that allowed for a crippling style of play would not go unnoticed by the press and the public who felt football had become a form of butchery, as men were routinely carried off of the field with broken bones and blood forced trauma. Navy and Army went so far as to cancel their annual game, with many other schools entertaining the idea of abolishing their football program all together. To make matter worse, the Intercollegiate Football Association comprised of only Princeton and Yale now, as football had expanded out to the mid west and the west coast and led to the creation of “leagues” based on geographical location. Therefore, no authoritative body could provide a resolution to these issues.

In the hopes of saving football, however, the University Athletic Club of New York invited representatives from Harvard, Pennsylvania, Princeton and Yale to establish a new football rules committee in 1894. Along with Walter Camp, the most reputable man at this committee was Paul J. Dashiell, who was regarded as the leading official of the game at the time. The committee went about it’s task by sending a questionnaire to all former players on the topic of injuries and football, and extended the invitation for anyone to offer suggestions as to what rule revisions could make the game safer.

After much deliberation, the committee decided on a handful rule changes: the most apparent and impactful revisions were the elimination of mass momentum plays, which was described as when more than three men, grouping more than five yards behind the line, started before the ball was put in play, and the requirement that on kick offs, the ball has to be kicked at least ten yards into the opponent’s side of the field to be put into play. Other revisions called for an additional official on the field and the reduction to seventy minutes of play from ninety minutes.

Woodruff’s Guards Back Formation

Making the most within the given rules, Woodruff immediately went to the drawing board, and once the 1894 season arrived he unleashed his new innovation known as the guards back formation. In this formation, the guards, at the signal given by the quarterback, withdrew from the positions at the line of scrimmage and entered into the backfield. One guard was about a yard and a half behind his normal line position, with the second guard about a yard behind him. The figure below shows and edge rush from this formation.

Furthermore, Woodruff also was a pioneer in the kicking game. As previously mentioned in part two of this series, players that were behind the kicker when he punted the ball were eligible to run down and recover the ball. With the ten yard minimum rule, the onside kick was now rising in popularity on the kick off. Woodruff took the onside kick and applied it to the scrimmage play. The guards back formation would bring defenders close to the line of scrimmage, leaving the side of the field wide open to recover a kick, as seen to the bottom left.

While these rulings were thought have been an answer to football’s problems, not all were prepared to accept these revisions. Public outcry was still demanding that any resemblance of a mass momentum play be outlawed. Princeton and Yale furthered implemented rules to appease the masses by forbidding more than one man to be in motion before the snap of the ball, and restricting more than three men from grouping behind the line. Harvard and Pennsylvania, among others, opted to have no restrictions behind the line of scrimmage. This created a system of regional based rules provided to cohesive guidelines for the game of football.

The Last of the Mass Formation

Once 1896 had arrived, college officials from all directions of the United States gathered to decide on a uniform set of rules for all universities to abide by in order to save football from it’s abolishment. They ultimately would not be able to get all of the colleges to agree, but those that did acknowledged the five new rules that were voted in, the most notable reading, “No player of the side in possession of the ball shall take more than one step toward his opponent’s goal before the ball is snapped without coming to a complete stop. At least five players shall be on the line of scrimmage when the ball is snapped. If six players are behind the line of scrimmage, then two of the said six players must be at least five yards behind the line or shall be outside of the players on the end of the line.”

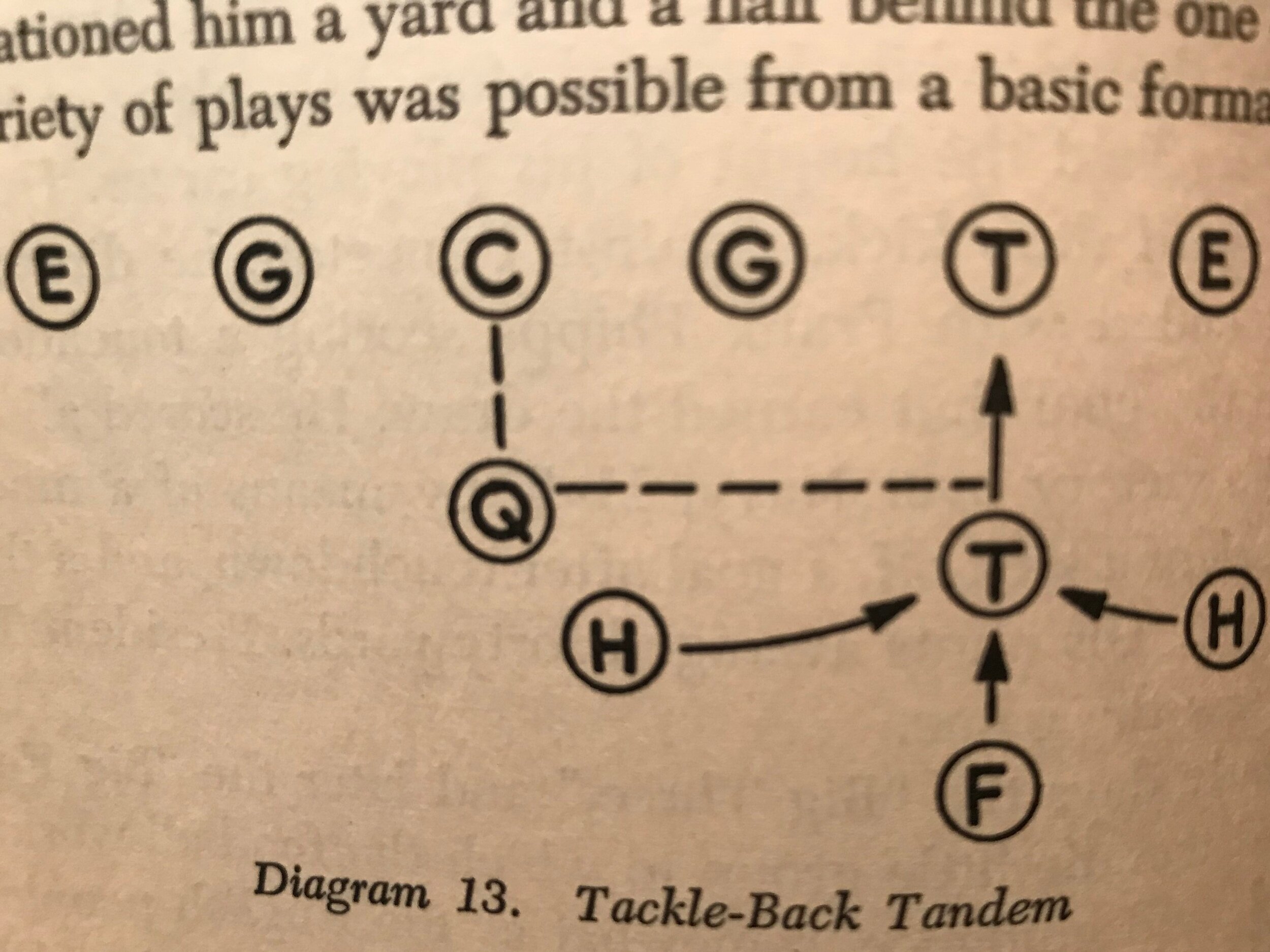

Thus, the last string of formidable mass formations in football would enter. The most notable formation was the tackle back formation. The formation is credited as being the invention famed Minnesota head coach Dr. Henry L. Williams, who conceived it officiating games while attending medical school at the William Penn Charter School. But again, Amos Alonzo Stagg claims to have invented it himself. Stagg, however, claims to have invented the tackles-back formation, which drew both tackles into the backfield, about one yard behind the guards and the backs placed another three yards behind them. Williams only drew one tackle into the backfield.

The genesis of the tackle back formation was risen out of the shortcomings of the guards back formation. First, due of the new rule, the guards back formation placed the depth of the backs about five yards behind the line of scrimmage, but with only one lineman drawn into the backfield, they didn’t have to worry about the distance of their alignment. Secondly, the guards were better suited for blocking at the point of impact on the line, as they were not the most athletic members on the team, so the tackle back formation allowed them to play to their strength.

To substitute the subtraction of size and strength from the guards back formation, Dr. William opted to use a tackle from the one side of the formation and stationed him a yard and half behind the tackle on the other side of the formation. This allowed Williams to keep six men on the line of scrimmage, and placed a powerful but athletic lineman in the backfield with heavy fullback to maintain the bruising impact of force seen from the guards back formation.

While Williams is credited with the invention of this formation, scholars point to Walter Camp as the coach who perfected it and brought out it’s potential. Camp added wrinkles to the formation by placing an additional lineman at the fullback position, and also conceived an early form of the trap play. At the time, defensive lineman were taught to play low and charge upfield on every play. Camp, seeing an opportunity, faked the ball to the tackle back that dove up the middle as the offensive lineman intentionally let them by, and then handed the ball to the back that took off upfield with blocking to protect him from the secondary chain of defense.

Another play that came in 1896 was the revolving tandem by Princeton. The play was drawn up by captain Philip King. In this formation, he placed the ends back a shade behind the tackle, but tight to the line. As the ball was snapped, the backfield jumped into an oval formation and revolved to the outside. This confused the defense as to who had the ball, as it was done much more swiftly than the turtleback formation that was introduced six years earlier.

Lastly, C.M. Hollister of Northwestern University created the Northwestern tandem a formation that would come to be known as the I Formation when revived by Illinois head Coach Bob Zuppke in 1914.

The Turn of the century

From 1896 to 1900, college football was able to enjoy a brief period free of controversy and wholesale rule changes. During this time, in fact, the most drastic changes would be a penalty for the center if he faked the snap to draw his opponents offsides, as well as some updates to the scoring values.

But in 1901, the criticism of football’s brutality began to enter the national conversation once again, but this time it was also criticized for for lack of professionalism and organization, as well as gambling and questionable academic standards for the players. The midwest in particular, headlined by the Chicago-Michigan rivalry, had turned football into a game of such challenging endurance with use of “hurry up” offenses, where teams would run nearly 200 plays combined at a time when substitution was forbidden. Many spectators and players from the previous generation were screaming for a return to the “open game” of football.

After a couple years of making modifications to rules that really didn’t bear much impact on the violent nature of the sport, the Rules Committee went to work again to find a solution. Wanting to find a balance between the open game and the current mass formation game, the Rules Committee put out the rule that from a team’s goal line to the 25 yard line, only five men were required to be on the line of scrimmage, while between the 25 yard lines, seven men were required to be on the line of scrimmage. Furthermore, the quarterback was now permitted to run with ball, but could not cross the original line of scrimmage until he ran five yards to the right or left from where the ball was snapped. This created the “checkerboard” fields to keep track of that yardage.

By 1904, however, the Rules Committee made it mandatory to have six men on the line of scrimmage at at all time, making the tackle back formation a base offense. Additionally, kicking rules were restricted, for any one who kicked the ball and ran past his teammates to put them onside would no longer be allowed to recover it.

With six men required to be on the line of scrimmage, the era of mass formation was coming to an end, eliminating elaborate and creative formations that would be outlawed for the rest of football’s history. But while the criticism that the sport received was severe enough to make this alter the rules to outlaw the mass formations, nothing would prepare for the 1905 crisis that would usher in a new brand of football completely.

In Part 4, we will explore the introduction of the forward pass and the final scrimmage rules that would transition football into the primitive form of the modern game.

REFERNECES

The Saga of American Football, Alexander M. Weyand, The Macmillan Company, 1955

Football: The Intercollegiate Game, Parke H. Davis, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911

Anatomy of a Game, David M. Nelson, University of Delaware Press, 1991

The History of American Football: It’s Great Teams, Players and Coaches, Allison Danzing, Prentice-Hall Inc, 1956